Processor : Intel Core 7 Processor 240H 2.5 GHz (24MB Cache, up to 5.2 GHz, 10 cores, 16 Threads)

Processor : Intel Core 7 Processor 240H 2.5 GHz (24MB Cache, up to 5.2 GHz, 10 cores, 16 Threads)

ASUS Gaming V16 (2025) WITH Large battery

76566 ₹ – 87990 ₹Price range: 76566 ₹ through 87990 ₹

Description

Large battery

The Large Battery: Powering the Present, Electrifying the Future

Introduction: The Silent Revolution

We live in an age of silent revolutions. While headlines are captured by flashy smartphones, artificial intelligence, and space exploration, a more fundamental transformation is occurring in the realm of energy storage. At the heart of this transformation lies the large battery. This term, once synonymous with the lead-acid behemoths under the hoods of our cars, has evolved to represent a diverse and rapidly advancing family of technologies that are becoming the linchpin of modern society. A large battery is no longer merely an energy storage device; it is an enabling technology for renewable energy, the cornerstone of electric mobility, a critical backup for global communications, and a key player in the fight against climate change.

Chapter 1: Defining and Classifying the Large Battery

What exactly constitutes a “large battery”? The definition is relative and contextual. Compared to a coin cell in a watch, a smartphone battery is large. In the energy sector, however, “large” scales to a completely different magnitude. We can classify them by application and scale:

1.1 By Application:

-

Stationary Energy Storage (ESS): These are fixed installations designed to store electrical energy for later use. They are the workhorses of the energy grid and for industrial backup. Their size can range from a small cabinet to a warehouse-sized facility.

-

Traction Batteries (E-Mobility): These are the batteries that propel electric vehicles (EVs), including cars, buses, trucks, scooters, and bicycles. They are characterized by high power density for acceleration and high energy density for long range.

-

Marine and Aerospace Batteries: Used in electric boats, ships, and aircraft, these batteries must meet extreme demands for safety, weight, and reliability in harsh environments.

-

Industrial Backup (UPS): Uninterruptible Power Supply systems use large battery banks to provide instantaneous power during grid outages, critical for data centers, hospitals, and financial institutions.

1.2 By Scale and Capacity:

-

Small-Scale Large Batteries (1-100 kWh): This includes residential solar storage systems (e.g., Tesla Powerwall) and the battery packs in most electric cars (e.g., 60-100 kWh packs).

-

Medium-Scale Large Batteries (100 kWh – 10 MWh): This encompasses commercial building storage, large EV charging station buffers, and community-level microgrids.

-

Grid-Scale Large Batteries (10 MWh and beyond): These are massive installations, often called “Battery Energy Storage Systems” (BESS), directly connected to the electrical grid. The largest facilities today exceed 1,000 MWh (or 1 GWh), capable of powering hundreds of thousands of homes for several hours.

The common thread is that a “large battery” is a complex system, not a single cell. It is a battery pack comprising hundreds or thousands of individual cells, managed by a sophisticated Battery Management System (BMS), and integrated with cooling, safety, and power conversion systems.

Chapter 2: The Core Technologies and Chemistry

The performance, cost, and safety of a large battery are dictated by its underlying chemistry. While research is exploring dozens of options, a few dominant technologies have emerged.

2.1 Lithium-Ion: The Reigning Champion

Lithium-ion (Li-ion) technology is the undisputed leader for most large-scale applications due to its high energy density, high efficiency, and declining cost.

-

How it Works: Li-ion batteries work on the principle of “intercalation,” where lithium ions shuttle back and forth between a positive electrode (cathode) and a negative electrode (anode) through an electrolyte. The specific materials used define the battery’s character.

-

Common Chemistries:

-

NMC (Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide): The dominant chemistry in EVs and energy storage. It offers a excellent balance of energy density, power, and lifespan. The push is to reduce cobalt content (NMC 811) due to its cost and ethical concerns.

-

LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate): Gaining massive market share, particularly for stationary storage and entry-level EVs. LFP batteries have a longer cycle life, superior safety (more thermally stable), and use cheaper, more abundant materials (iron, phosphate). Their main drawback is slightly lower energy density than NMC.

-

NCA (Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Oxide): Similar to NMC, used prominently by Tesla, offering very high energy density.

-

2.2 The Challengers and Complements

While Li-ion dominates, other technologies serve specific niches or offer promise for the future.

-

Lead-Acid: The venerable technology is not dead. Its low upfront cost and high recyclability make it still relevant for automotive starting batteries and some low-cost backup systems. However, its poor energy density, weight, and short cycle life disqualify it from most modern large-scale applications.

-

Flow Batteries: A fundamentally different approach ideal for long-duration grid storage (8+ hours). Instead of storing energy in electrode material, energy is stored in liquid electrolytes housed in external tanks. Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries (VRFB) are the most commercialized. Their key advantage is that power (size of the stack) and energy (size of the tanks) can be scaled independently, and they can cycle daily for 20+ years with minimal degradation.

-

Sodium-Ion (Na-ion): Emerging as a potential “drop-in” replacement for LFP. Sodium is far more abundant and cheaper than lithium. While early Na-ion batteries had lower energy density, recent advancements have made them competitive for stationary storage and lower-range EVs, offering a compelling, low-cost alternative.

-

Solid-State Batteries: The “holy grail” of battery technology. These replace the flammable liquid electrolyte with a solid material (ceramic, polymer). This promises revolutionary improvements: higher energy density (enabling longer-range EVs), dramatically improved safety (no fire risk), and faster charging. While commercially viable solid-state batteries are still several years away, they represent the most anticipated future breakthrough.

Chapter 3: Monumental Applications Reshaping Our World

The impact of large batteries is being felt across the global economy and infrastructure.

3.1 Enabling the Renewable Energy Transition (The “Green Grid”)

This is arguably the most critical application. Solar and wind power are intermittent—the sun doesn’t always shine, and the wind doesn’t always blow. Large batteries solve this problem.

-

Time-Shifting Energy: Batteries store excess solar energy generated at noon and release it during the evening peak demand, a process called “peak shaving.”

-

Grid Stabilization: They provide “ancillary services” to the grid, such as frequency regulation, by absorbing or injecting power in milliseconds to maintain the grid’s delicate balance between supply and demand. This is far faster and cleaner than ramping a fossil-fuel plant up and down.

-

Renewables Firming: They ensure a smooth, reliable output from a solar or wind farm, making it a more dependable source of power for utilities.

3.2 Electrifying Transportation (The E-Mobility Revolution)

The automotive industry is undergoing its most significant shift in a century, driven entirely by the large traction battery.

-

Passenger EVs: From sedans to SUVs, the battery pack is the most critical and expensive component, defining the vehicle’s range, performance, and cost.

-

Commercial Vehicles: Electric buses, delivery vans, and semi-trucks are becoming commonplace. Their large battery packs require ultra-fast charging solutions and are optimized for durability over thousands of deep cycles.

-

Beyond Roads: The revolution extends to electric boats (ferries, pleasure craft), mining equipment, and even short-haul aircraft (eVTOLs), all reliant on advanced, high-power battery systems.

3.3 Ensuring Resilience and Reliability

In an increasingly digital and interconnected world, power outages are catastrophic.

-

Data Centers: The backbone of the internet and cloud computing, data centers use massive UPS systems with large battery banks to prevent milliseconds-long interruptions that could cause worldwide service disruptions and data loss.

-

Hospitals and Critical Infrastructure: Life-saving equipment, surgical suites, and emergency systems cannot afford a loss of power. Battery backups provide seamless transition during an outage.

-

Home and Business Backup: With increasing grid instability due to extreme weather events, residential and commercial battery systems paired with solar panels are creating “energy-independent” homes and businesses.

Chapter 4: The Formidable Challenges and Limitations

Despite their promise, large batteries face significant hurdles that must be overcome for their sustainable and widespread adoption.

4.1 The Raw Material Conundrum

The skyrocketing demand for batteries has created a supply chain crunch for critical minerals.

-

Lithium and Cobalt: Mining these materials is geographically concentrated (e.g., lithium in Australia and Chile, cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo), raising concerns about geopolitical risks, price volatility, and in the case of cobalt, ethical issues around mining practices.

-

Environmental Impact of Mining: The extraction processes can be water-intensive and polluting, creating a paradox where a technology meant to help the environment causes local ecological damage. Lifecycle analysis (LCA) is crucial to ensure the net environmental benefit is positive.

4.2 Cost and Economics

While the cost of Li-ion batteries has fallen dramatically (by over 90% in the last decade), the upfront capital expenditure for a large battery system remains significant. The business case depends on complex factors like electricity price arbitrage, government incentives, and the value of grid services provided.

4.3 Safety and Thermal Runaway

A damaged or defective Li-ion cell can enter a state called “thermal runaway”—an uncontrollable, self-heating chain reaction that can lead to fires or explosions that are difficult to extinguish. While rare, high-profile incidents (EV fires, grid storage facility fires) highlight the need for relentless engineering in the BMS, cooling systems, and containment designs to mitigate this risk.

4.4 Degradation and End-of-Life

A battery does not last forever. Its capacity diminishes with each charge-discharge cycle and over calendar time. After 8-15 years, a large battery may no longer be suitable for its primary purpose. This creates the challenge of:

-

Second-Life Applications: A retired EV battery with 70% capacity can still be used for less demanding stationary storage for another decade, a concept known as “second-life.” This requires sophisticated testing, repackaging, and business models.

-

Recycling: Ultimately, batteries must be recycled to recover valuable materials (lithium, cobalt, nickel) and create a circular economy. Recycling technology is advancing but is not yet universally economical or scalable to handle the coming tidal wave of end-of-life batteries.

Chapter 5: The Future Horizon – Innovations on the Way

The development of large batteries is a frontier of intense scientific and industrial activity. The future promises even more powerful, safer, and cheaper solutions.

5.1 Next-Generation Chemistries

-

Solid-State Batteries: As mentioned, this is the flagship future technology. Major automakers and startups are investing billions to solve manufacturing challenges and bring solid-state batteries to market, potentially doubling the range of EVs.

-

Lithium-Sulfur (Li-S): Offers a theoretical energy density much higher than Li-ion. Sulfur is abundant and cheap. The challenge lies in the short cycle life due to the degradation of the sulfur cathode, but progress is being made.

-

Sodium-Ion and Other Post-Lithium Chemistries: Research into batteries based on magnesium, zinc, and aluminum continues, seeking to move beyond the limitations of lithium.

5.2 Manufacturing and System Innovations

-

Gigafactories: The scale of production is itself an innovation. Massive factories like Tesla’s Gigafactory are driving down costs through economies of scale, advanced automation, and vertical integration.

-

Cell-to-Pack (CTP) Technology: This design innovation removes intermediate modules and integrates cells directly into the pack, increasing energy density, simplifying manufacturing, and reducing cost. BYD’s Blade Battery and CATL’s Kirin battery are prime examples.

-

AI-Optimized Battery Management: Using artificial intelligence and machine learning to manage charging/discharging strategies in real-time, predicting failure, and maximizing the lifespan and performance of each individual cell within a massive pack.

5.3 The Circular Economy

The future will be defined by a closed-loop system for batteries. This involves:

-

Design for Recycling: Manufacturers will design batteries from the start to be easily disassembled.

-

Advanced Hydrometallurgical Recycling: Processes that can efficiently recover over 95% of valuable metals with a lower environmental footprint than traditional methods.

-

Standardization and Regulation: Governments will implement strict Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) laws, forcing manufacturers to take back and recycle their products.

Conclusion: The Centerpiece of a Sustainable Future

The large battery is far more than a simple component; it is a foundational technology of the 21st century. It is the critical enabler that allows us to harness the power of the sun and wind, to break our dependence on fossil fuels for transportation, and to build a more resilient and digital world. The challenges of resource scarcity, cost, and end-of-life management are substantial, but they are being met with unprecedented levels of investment, innovation, and regulatory focus.

The Large Battery: The Unseen Engine of a Global Transformation

Introduction: The Pivotal Shift from Energy Consumer to Energy Hub

We are living through a paradigm shift as profound as the industrial revolution, yet it is largely silent and unseen. This shift is centered on our relationship with energy: how we generate it, how we use it, and most critically, how we store it. At the heart of this transformation lies the large battery. This term, which once conjured images of the simple, heavy lead-acid block starting a car’s engine, has evolved to represent a sophisticated, dynamic, and intelligent system that is rapidly becoming the linchpin of modern civilization. A large battery is no longer a passive container of energy;

Chapter 1: Defining the Scale – What Constitutes a “Large Battery”?

The definition of “large” is inherently relative and contextual. Compared to the milliampere-hour (mAh) capacity of a hearing aid battery, a smartphone battery is large. In the realm of energy infrastructure and electric mobility, however, “large” scales to an entirely different order of magnitude. We can classify these systems by their application, physical scale, and energy capacity.

1.1 Classification by Application and Function:

-

Stationary Energy Storage Systems (ESS): These are fixed installations designed to store electrical energy on a significant scale for later use. They are the workhorses of the modern electrical grid, renewable energy farms, and industrial facilities. Their function can be further broken down into:

-

Front-of-the-Meter (FTM): Large-scale systems directly connected to the transmission or distribution grid, owned and operated by utilities or independent power producers. Their primary roles include grid stabilization, frequency regulation, and deferring costly infrastructure upgrades.

-

Behind-the-Meter (BTM): Systems installed at a consumer’s site, such as a home, business, or factory. Their purposes include maximizing self-consumption of solar power, providing backup power during outages, and reducing electricity costs through peak shaving (drawing from the battery during periods of high, expensive grid demand).

-

-

Traction Batteries (E-Mobility): These are the high-performance batteries designed for propulsion. They power the electric revolution in transportation, from light-duty vehicles to heavy machinery. Their key characteristics are high power density (for acceleration and climbing) and

Additional information

| COLOUR | BLACK Core 5 210H, BLACK Core 7 240H |

|---|

Related products

-

Sale!

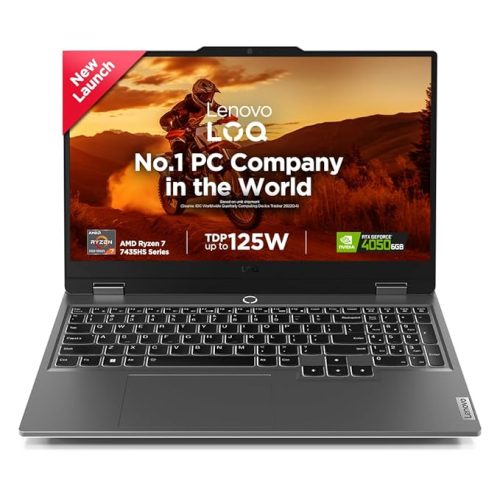

Lenovo Smartchoice LOQ AMD Ryzen 7 7435HS, NVIDIA RTX 4050-6GB, 24GB RAM, 512GB SSD, 15.6″/39.6cm, Windows 11, MS Office Home 2024, Grey, 2.4Kg, 83JC00EGIN, 100% sRGB, 3 Mon. Game Pass Gaming Laptop with fast charging

110890 ₹Original price was: 110890 ₹.81490 ₹Current price is: 81490 ₹. -

Sale!

HP Victus, 13th Gen i7-13620H, 6GB RTX 4050 (16GB DDR4, 512GB SSD) FHD, 144Hz, IPS, 15.6”/39.6cm, Win11, M365* Office24, Mica Silver, 2.29kg, fa2100TX/2103tx, Backlit, Enhanced Cooling, Gaming Laptop with Smart Technology

103018 ₹Original price was: 103018 ₹.87990 ₹Current price is: 87990 ₹. -

Sale!

HP Omen 16 Max,Intel Ultra 9 275HX,12GB NVIDIA RTX 5070 Gaming AI Laptop (32GB DDR5,1TB SSD) 60-240 Hz,3Ms,IPS,WQXGA,16”/40.6Cm,Win11,M365 Basic (1year), Office24,Black,2.75Kg,RGB Backlit,ah0190TX WITH WQXGA Display

314752 ₹Original price was: 314752 ₹.272990 ₹Current price is: 272990 ₹.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.